The Frankfurt Kitchen

War and inflation precipitated a housing crisis in all major German cities, including Frankfurt, where the response was an ambitious program known as the New Frankfurt. This initiative encompassed the construction of affordable public housing and modern amenities throughout the city. At the core of this transformation were about 10,000 kitchens designed by Grete Schütte-Lihotzky and constructed as an integral element of the new dwelling units.

The Frankfurt Kitchen, as it was known—rational, unpretentious, and socially oriented—was conceived as one of the first steps toward building a better, more egalitarian world in the late 1920s. Under the overall direction of chief city architect Ernst May, new architectural forms, new materials, and new construction methods were applied throughout. Within five years, more than ten percent of Frankfurt’s population was living in housing and communities that were newly designed. In 1930, at the request of the Soviet Russian government, May led a “building brigade,” whose members included Schütte-Lihotzky, to implement the lessons of Frankfurt on an even larger scale in the planning of new industrial towns in the Soviet Unio

The Frankfurt Kitchen is the earliest work by a female architect in MoMA’s collection. Reminiscing about her decision to study architecture, Schütte-Lihotzky remarked that “in 1916 no one would have conceived of a woman being commissioned to build a house—not even myself.” Inspired by her mentor at the Vienna School of Applied Arts, Oskar Strnad, she became involved in designing affordable housing and worked with another Viennese architect, Adolf Loos, on planning settlements for World War I veterans.

Impressed by the functional clarity that she applied to housing problems and kitchen design in these projects, Ernst May invited her to join his Frankfurt department in 1926. She remains best known for the Frankfurt Kitchen, but her achievements as an architect working in the Soviet Union, Turkey, and Austria were more varied. During World War II her career was interrupted by four years in prison for her activities in the anti-Nazi resistance movement. In the Cold War period that followed, her professional opportunities in Austria were limited because of her continued membership in the Communist Party.

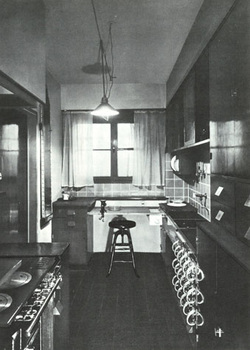

The Frankfurt Kitchen was designed like a laboratory or factory and based on contemporary theories about efficiency, hygiene, and workflow. In planning the design, Schütte-Lihotzky conducted detailed time-motion studies and interviews with housewives and women’s groups.

Each kitchen came complete with a swivel stool, a gas stove, built-in storage, a fold-down ironing board, an adjustable ceiling light, and a removable garbage drawer. Labeled aluminum storage bins provided tidy organization for staples like sugar and rice as well as easy pouring. Careful thought was given to materials for specific functions, such as oak flour containers (to repel mealworms) and beech cutting surfaces (to resist staining and knife marks).

After reading Christine Frederick’s book on household efficiency in 1921, Schütte- Lihotzky became convinced that “women’s struggle for economic independence and personal development meant that the rationalization of housework was an absolute necessity.” Her primary goal in the design of the Frankfurt Kitchen was to reduce the burden of women’s labor in the home. The design of a kitchen by a woman helped promote the modernization of housing in Frankfurt to those who viewed cooking and cleaning as women’s work, but as Schütte-Lihotzky pointed out, “The truth of the matter was, I’d never run a household before designing the Frankfurt Kitchen, I’d never cooked, and had no idea about cooking.” The Frankfurt Kitchen comprised three basic models, each with minor variations. The type exhibited here was the most common and least costly.

http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2010/counter_space/the_frankfurt_kitchen

The Frankfurt Kitchen, as it was known—rational, unpretentious, and socially oriented—was conceived as one of the first steps toward building a better, more egalitarian world in the late 1920s. Under the overall direction of chief city architect Ernst May, new architectural forms, new materials, and new construction methods were applied throughout. Within five years, more than ten percent of Frankfurt’s population was living in housing and communities that were newly designed. In 1930, at the request of the Soviet Russian government, May led a “building brigade,” whose members included Schütte-Lihotzky, to implement the lessons of Frankfurt on an even larger scale in the planning of new industrial towns in the Soviet Unio

The Frankfurt Kitchen is the earliest work by a female architect in MoMA’s collection. Reminiscing about her decision to study architecture, Schütte-Lihotzky remarked that “in 1916 no one would have conceived of a woman being commissioned to build a house—not even myself.” Inspired by her mentor at the Vienna School of Applied Arts, Oskar Strnad, she became involved in designing affordable housing and worked with another Viennese architect, Adolf Loos, on planning settlements for World War I veterans.

Impressed by the functional clarity that she applied to housing problems and kitchen design in these projects, Ernst May invited her to join his Frankfurt department in 1926. She remains best known for the Frankfurt Kitchen, but her achievements as an architect working in the Soviet Union, Turkey, and Austria were more varied. During World War II her career was interrupted by four years in prison for her activities in the anti-Nazi resistance movement. In the Cold War period that followed, her professional opportunities in Austria were limited because of her continued membership in the Communist Party.

The Frankfurt Kitchen was designed like a laboratory or factory and based on contemporary theories about efficiency, hygiene, and workflow. In planning the design, Schütte-Lihotzky conducted detailed time-motion studies and interviews with housewives and women’s groups.

Each kitchen came complete with a swivel stool, a gas stove, built-in storage, a fold-down ironing board, an adjustable ceiling light, and a removable garbage drawer. Labeled aluminum storage bins provided tidy organization for staples like sugar and rice as well as easy pouring. Careful thought was given to materials for specific functions, such as oak flour containers (to repel mealworms) and beech cutting surfaces (to resist staining and knife marks).

After reading Christine Frederick’s book on household efficiency in 1921, Schütte- Lihotzky became convinced that “women’s struggle for economic independence and personal development meant that the rationalization of housework was an absolute necessity.” Her primary goal in the design of the Frankfurt Kitchen was to reduce the burden of women’s labor in the home. The design of a kitchen by a woman helped promote the modernization of housing in Frankfurt to those who viewed cooking and cleaning as women’s work, but as Schütte-Lihotzky pointed out, “The truth of the matter was, I’d never run a household before designing the Frankfurt Kitchen, I’d never cooked, and had no idea about cooking.” The Frankfurt Kitchen comprised three basic models, each with minor variations. The type exhibited here was the most common and least costly.

http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2010/counter_space/the_frankfurt_kitchen